|

|

|

|

|

The Settlement at Madawaska

Historically, Wadawaska is the name initially given to what is now known as the St. John

River. Today, one of its tributaries carries that name.

In 1782, a 14 year-old French-Canadian boy named Pierre Lizotte, lost in the woods of what is now

Quebec, crossed to the mouth of the Madawaska River where he came across a village of Maliseet Indians, spending the winter with them. A couple of years later, along with his half-brother, Pierre Duperre, he

returned to Madawaska to establish a trading post. The following year they located on the south bank of the St. John, a mile or two below the Indian village. Lizotte and Duperre may have been the first

permanent white settlers in Aroostook County, although this cannot be determined with a degree of accuracy. It was, at least, the first Acadian settlement in Madawaska.

|

|

|

|

In February of 1785, Pierre Duperre sent a letter to the Canadian government requesting

grants of land at Madawaska for 25 heads of families, including Louis Mercure, Pierre Duperre, Jean-Baptiste Cyr, and Joseph Daigle. Cyr had already petitioned the Governor-General for grants for

himself and for his nine sons.

The following June, as a precautionary measure, Daigle applied for similar grants to the government of the recently organized province of New Brunswick. The Madawaska region was already in dispute between New Brunswick and Quebec.

|

|

|

|

|

|

In June of 1785, several Acadian families crossed the river, beginning a settlement on both banks

just below the mouth of the Madawaska. They were reportedly on good terms with the Maliseets, and enjoyed a relationship of mutual trade.

During the summer the settlers chose their homesteads, built homes, planted grain and potatoes, and gathered feed for the cattle that they planned to bring up the river in the fall. Among those who located on the south bank of the St. John were Pierre Duperre, Paul Potier, Joseph Daigle, Baptiste Fournier, Joseph Daigle Jr., Jacques Cyr, Francois Cyr, Fermin Cyr, Alexandre Ayotte, Antoine Cyr, Baptiste Thibodeau, and Louis Sansfacon. Louis Mercure and his brother Michael settled on the north bank near their trading post. The others came the following summer, and by the third season the settlement consisted of some twenty families.

|

|

|

|

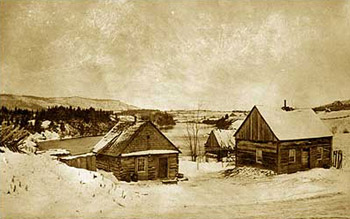

Their cabins, built of logs and roofed with bark, had a single room with one or two

windows, usually facing south, as the harshest winds came from the north. Fireplaces, with stone chimneys, burned a lot of wood, gave light, but generated little in the way of heat.

|

|

|

Furniture was handmade, and sparse, including a table, a few wooden seats, a couple of chairs, beds

and, for the children, trundle beds that were opened at night but could be hidden away during the day.

Tableware usually was made of wood. The settlers grew grain and potatoes, but largely depended on hunting and fishing. Clothing also was primitive, including jackets made from caribou skins, deerskin pants, and moccasins made of moosehide. Imported goods were expensive, since they had to be brought in on foot or by canoe.

|

|

|

|

|

|

A few years passed before the settlers received the requested grants of land, but in

1790 the New Brunswick government granted them land on both sides of the St. John River, between Green River and the Madawaska.

Four years later, a second grant of more than 5,000 acres below Green River to 25 other settlers. Among the family names found in these grants are those still common in northern Aroostook today, including

|

|

|

|

|

Cormier, Cyr, Daigle, Dube, Hebert, Marquis, Martin, Michaud, Theriault, Thibodeau, and

Violette. By 1792, the settlement had grown large enough to petition the Bishop of Quebec for permission to construct a church.

The request was granted, and the church, dedicated to St. Basil, was built on the north side of the St. John River, a few miles south of Madawaska. It was not until the 1830s that a church was built on the American side.

Life was not easy, and the settlers at Madawaska were often near starvation.

1797 was particularly rough. For two years, the crops had been damaged by spring floods and early frosts, followed by unusually harsh winters. At one point, after the men had been unable to return from a hunting expedition due to a sudden snowstorm, they returned to find that the women and children had been forced to kill the last cow, and to eat the last of the grain. Fortunately, their hunting expedition had been productive, and they had brought meat back to their families.

|

|

|

|

One woman, Marguerite Blanche Cyr, the wife of Joseph Cyr, became known for heroism

during this time of famine, and was given the title of "La Tante du Madawaska” (Aunt of Madawaska). An aunt to several nephews and nieces, she became in spirit, an aunt to the entire region.

|

|

|

|

|

|

She is said to have been a particularly strong and charitable woman, bringing food and clothing to

those who were most in need; and became the object of esteem bordering on worship. She was said to have cured diseases, resolved family disputes, found lost articles, and to have brought enemies

together. Upon her death, she was buried within the walls of the church at St. Basil.

|

|

|

|

While the War of 1812 was in progress, Monseigneur Plessis, the Bishop of Quebec, made a pastoral

visit to Madawaska. Traveling by canoe from the Bay of Chaleur by way of the Restigouche, Waghensis and Grand Rivers, and departed by the regular route up the Madawaska River, and by land to the St. Lawrence

River. His trip was a difficult one.

For miles along the Waghensis, hanging branches whipped and troubled him. The trip between the Waghensis and Grand Rivers was uncomfortable and much longer than he expected. When he finally reached the Grand River, where he was to have been met by canoes for the remainder of the trip, no canoes awaited him, and his food was almost gone. By the time he reached St. Basil, he was exhausted and in poor temper.

His written opinion of Madawaska was not at all flattering. The settlement had grown to 110

families. According to Monseigneur Plessis, the inhabitants were rude and ignorant, outcasts from Canada and Acadia.

He wrote that they were stubborn, hard to lead, and suggested they had worn out the patience of the good priests who had served them. he reported that their fields were fertile, but that they had no roads or adequate communication with the outside world. Moreover, he said there were no salmon in the river above Grand Falls.

The Monseigneur concluded that Madawaska belonged to the United States under the terms of the Treaty

of 1783.

And in fact, the British did not deny the terms of that treaty, but held the country in reprisal for English territory they claimed were occupied by Americans elsewhere. Most Madawaskans had refused to enroll in the British militia, not particularly fond of the English and uncertain as to whom they owed their allegiance.

|

|

|