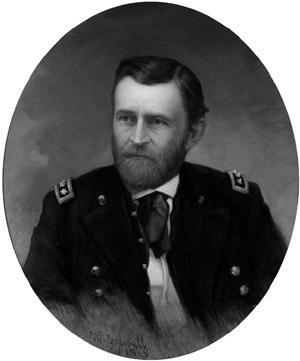

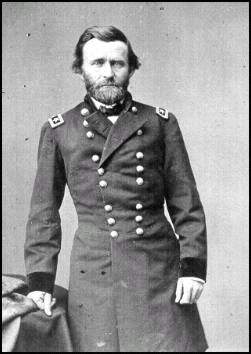

General Ulysses S. Grant

Grant was born on April 27, 1822 in Point Pleasant, Ohio. His real name was Hiram Ulysses Grant, the name that he answered to until he was enrolled at West Point. The Congressman who appointed him had completed the application in the name of Ulysses S. Grant. When Grant arrived at West Point and learned that the academy had registered him under the wrong name, he tried to get the error corrected, but he was told that the application could not be changed, and finally decided that it was easier to change his name to match the application.

Although he was an expert horseman, he was unable to join the Cavalry because he graduated West Point 22nd in a class of 39. Instead, he joined the 4th Infantry Regiment as a 2nd Lieutenant, and served as a regimental quartermaster during the Mexican War.

After the war, he was stationed on the Pacific Coast, where he developed a drinking problem that led to his resignation from the army in 1854.

Penniless, he turned to his wealthy West Point classmate, Simon Buckner, who guaranteed his hotel bill.

He worked as a firewood peddler, real estate salesman, and farmer near St. Louis, before becoming a clerk in his familyís tannery in Galenta, Illinois.

As an opponent of slavery, Grant offered his services to the Union army upon the outbreak of the American Civil War, and was commissioned as a Colonel in the 21st Illinois Volunteers.

He was promoted to Brig. General and placed in charge of the District of Southeast Missouri even before he had engaged the Confederate forces for the first time.

On September 4, 1861, General Polk and a large contingent of Confederate forces moved into Kentucky and occupied high ground overlooking the Ohio River, prompting Grant to moved his troops into Kentucky in order to gain control of the mouths of the Tennessee and Cumberland rivers as they flowed into the Ohio, thus allowing the Union to control the main waterway into the heart of the Confederacy.

In early February of 1862, Grant took a force of as many as 20,000 troops, supported by a flotilla of ironclads and gunboats, along the Tennessee River and captured Fort Henry.

This broke the Confederate communications line and prompted Confederate General Johnston to withdraw his army to Nashville, leaving a garrison of about 16,000 troops to defend Fort Donelson, located on the Cumberland River only about 10 miles from Fort Henry.

Only days after taking Fort Henry, Grant moved on Fort Donelson, forcing the surrender of Confederate General Simon Buckner, once a classmate and benefactor of Grant.

The battle of Fort Donelson was the first major victory for the Union after more than a year of fighting, bringing fame to Grant, proclaimed as the Northís new hero.

The Confederates regrouped. General Johnston and Beauregard reunited their armies at the Tennessee-Mississippi border. With 55,000 Confederate troops, they outnumbered Grantís strength. The Confederates attacked Grant at Shiloh on April 6th, causing heavy losses among the Union forces until they were reinforced by General Buellís troops.

Shiloh was one of the bloodiest battles of the war for the Union, and it resulted in complaints that Grant was responsible for the heavy casualty rate. General Halleck was mostly responsible for convincing President Lincoln that Grant was neverthless the right man for the job.

Shiloh was one of the bloodiest battles of the war for the Union, and it resulted in complaints that Grant was responsible for the heavy casualty rate. General Halleck was mostly responsible for convincing President Lincoln that Grant was neverthless the right man for the job.

Next came rumors that Grant was drinking heavily again, but they were found to be untrue.

Grantís next major objective was Vicksburg, a key Confederate city on the Mississippi, defended by General Pemberton, an able Confederate leader. After two failed assaults, Grant decided on a plan to starve them out. This worked, and on July 4, 1863, Pemberton surrendered.

The loss of Vicksburg cut the Confederacy in two, and Grantís successes in the West boosted his reputation even further, leading to Grantís appointment as General in Chief of the Union Armies in March of 1864.

Grant directed Sherman to drive through the South while he, with the Army of the Potomac, pinned down Leeís troops in northern Virginia. On April 9, 1864, Lee surrendered at Appomattox. The rest of the Confederacy soon followed.

During the course of the war, General Grant had several disagreements with President Lincoln. He defended generals such as Benjamin Butler, Nathaniel Banks, and Henry Thomas, whom Lincoln wanted to remove from command. Grant and Lincoln also disagreed about the strategies employed in the Shenandoah Valley, stating at one time that if the war had been left up to the military, it would have been over in a year.

In August of 1867, President Andrew Johnson sacked Edwin Stanton and appointed Grant as Secretary of War. When Congress began to insist that Stanton be reinstated, Grant resigned.

The following year, Grant ran as a Republican candidate for President, and was elected with 52.7% of the vote. At 46, Grant was the youngest man to be elected President.

Politically inexperienced, he is not considered to have been one of the nationís great presidents. He had trouble dealing with Congress, but was popular enough among the people to be elected to a second term.

His second term was plagued with scandal. He was accused of accepting lavish gifts from admirers, and was associated with people with tarnished reputations.

When Grantís second term came to an end in 1877, he became a partner in an investment firm, invested heavily in it on to have it go bankrupt nevertheless. His own reputation was further damaged when it was found that his partner was guilty of corruption associated with the firm.

He died on July 23, 1885 after suffering for years with cancer of the throat.