Ball’s Bluff

By October of 1861, the War between the States had been going on for six months. While many in the North had entered the war convinced that it would soon be over, they had yet to win a major battle.

Morale that was lost to the North was gained in the South. Their confidence buoyed by early victories, Southerners who may have entered the war with pessimism were now looking forward to winning their independence from the North.

In command of the Union forces, General George B. McClellan was pressured to do take some action to restore Northern hope. The Union needed a victory.

The armies on both sides were inexperienced, as many of the veterans of Fort Sumter, Bull Run, and Wilson’s Creek had been replaced with new recruits. Their line officers, some of whom had been newly elected or politically appointed, needed to learn to command soldiers in combat.

The common soldier on either side expected little in the way of action until spring, and were content to settle in for the winter. Nor were their commanders particularly eager to make any spectacular moves. Certainly, McClellan couldn’t afford another defeat, and the Confederate leaders were concentrating on building up their strength.

General Joseph Johnston, commanding the Confederate forces, realized that while his own forces were limited, McClellan was receiving new recruits for the defense of the Union capital. With the Potomac River as the dividing point, the Confederate forces were being consolidated into what was hoped to be a stronger fighting force, but there are no indications that he was planning an offensive before spring.

Although they were large in numbers, the true strength of the Union was in question. Washington D.C. was the Union capital, yet it was inside the Southern sphere of influence. If a vote were to have been taken among the civilian population of the Union capital, it would have favored the South.

In charge of the Union advance into Virginia was Brig. General Charles Stone. While a Colonel in charge of protecting the capital, Stone had uncovered and foiled a plot to assassinate President Lincoln at his inauguration. After secessions began, Stone was instrumental in securing the capital for the Union by taking control of the telegraph office and railroad, placing guards at each of the bridges leading into the city, and closing the Potomac to shipping traffic.

As a reward for his quick thinking, Lincoln promoted him to Brig. General, and he was thought to be on the fast track to promotion.

Neither the commanders of the North or of the South felt that it was in their better interests to begin a large advance before spring.

Union losses had resulted in enormous political pressure being put on McClellan to produce a victory, and the strong Southern sympathies within the capital itself resulted in questions about whether the Union army itself may be compromised.

On the other side, the situation was different. While the Confederate government was perfectly content to sit out the winter, it couldn’t help but note the pressure that was being placed on McClellan in the North, and took steps to fortify its own positions.

Johnston recalled his advanced outposts in northern Virginia intending to establish a stronger position against an anticipated Union advance.

McClellan sent Union troops to occupy the abandoned positions, increasing the Union presence on the Confederate side of the Potomac.

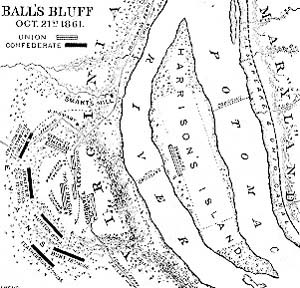

One position not abandoned by the Confederates was Leesburg, about 35 miles from the Union capital. Whoever had control of Leesburg had control of valuable river crossings, as well as the rail and communications link to the Shenandoah Valley.

Rather than pulling back from Leesburg, the Confederate base was fortified. Divisions under the command of Colonels Hunton, Barksdale, Featherstone, and Jenifer were brought together to form the 7th Brigade of the Confederate Army of the Potomac, under the immediate command of Brig. General Nathan Evans, and the overall command of General Pierre Beauregard.

McClellan decided that an advance on Leesburg would serve to satisfy the demands that were being placed on him for a victory, and believed that it could be accomplished with little or no heavy fighting.

Across the Potomac, on the Union side, were the armies commanded by Brig. General Stone. His troops were aptly named the Corps of Observation, as their chief responsibility was to guard the approaches to the Potomac in an area that ranged from the Point of Rocks, 10 miles north of Leesburg, to Edward’s Ferry, where the Potomac could be crossed at a direct road to Leesburg.

Additional Union troops, under the command of General George McCall, were already across the Potomac in Virginia.

The Battle of Ball’s Bluff began on October 19th when General McClellan ordered McCall to take his troops inland to Dranesville, about 15 miles southeast of Leesburg.

The movement was accomplished without difficulty, and it appeared to the Union forces that the Confederates were retreating from Leesburg.

McClellan saw this as an opportunity to be exploited. On October 20th, he sent word to General Stone at Poolesville advising him that McCall was moving on Dranesville, and asking Stone to make a “slight demonstration” across the Potomac to help move the Confederates along.

But it was a trick. Confederate forces had intercepted a Union courier carrying a dispatch from General McCall to General Meade of the Pennsylvania Reserves, asking him to watch the roads leading to Leesburg. From the courier, Evans had learned of the Confederate position near Dranesville.

Evans decided to set a trap.

General Stone planned to feign a movement across the Potomac at Edward’s Ferry with one brigade, while his main force began a flanking movement a few miles upriver, hoping to catch the Confederates between his troops on the left and McCall’s troops on the right.

on the left and McCall’s troops on the right.

Stone had intended to send a small recon party of about 20 volunteers under the command of Colonel Devens to secure Harrison’s Island, in the middle of the Potomac opposite a location in Virginia known as Ball’s Bluff, a steep ridge overlooking the river. Colonel Devens couldn’t be easily located, so it was nearly sunset before they got started. Devens chose a Captain Philbrick to lead the recon party.

Because of its rocky terrain, Ball’s Bluff had been left unguarded by the Confederates. Stone knew this, as previous recon parties had been to the location and knew of a cowpath leading up from the shore, the path they intended to take.

But with 20 inexperienced volunteers led by a Captain on his first night reconnaissance, on a foggy night, things didn’t go as planned.

Coming upon what they thought to be about 30 tents in a field, the recon party hurried back to Harrison’s Island to report to Colonel Devens on what they had seen. Devens, of course, reported this information to General Stone.

Stone decided to send Devens and his troops across the Potomac from his position on Harrison’s Island for the purpose of destroying the Confederate encampment. Colonel Raymond Lee and his forces were sent along for support.

By now, it’s after midnight. Finding the Potomac swollen by recent rains, Devens has only 3 boats by which to cross his 400 troops, so it was not until 4:00 a.m. on October 21st when Devens and his troops are finally across, to be followed by Colonel Lee’s forces. The men are tired, it’s still dark, and they have to struggle up a narrow cowpath to the top of the bluff.

By the time they arrive at what was thought to have been a Confederate camp, there is enough light to see that no such camp exists. Seeing haystacks in the fog and the dark, piled in a teepee formation, the recon troops had thought them to be tents.

Devens decides to continue on to a point just outside of Leesburg, and finds it seemingly abandoned. He sends word to Stone at Edward’s Ferry, suggesting that they be allowed to move on to Leesburg and take the town.

Stone decides against going along with Deven’s plan. Instead, he sends Colonel Edward Baker with a portion of his infantry brigade to take command of the situation.

Colonel Baker was no ordinary officer. He was a Senator and a close friend of President Lincoln. Through his political connections, he had secured his commission in the Union army even while he retained his Senate seat.

Crossing from Harrison’s Island, Baker and his larger force still had only the three boats in which to cross his 1,700 troops. And worse, unfamiliar with the area he was unaware of the 100 foot cliff called Ball’s Bluff, and didn’t even know about the cowpath.

Meanwhile, Deven’s troops were discovered by Confederate forces. Devens and his covering force, the 20th Massachusetts, are forced to fall back.

By the time Baker and his troops are finally able to reach the Virginia shore, Devens has already been under attack for more than seven hours.

Reaching Devens, Baker takes command; but, with little or no military experience or knowledge of military tactic, and facing four regiments of Confederate troops firing from the cover of a  wooded knoll above the bluff, the situation is hopeless.

wooded knoll above the bluff, the situation is hopeless.

Baker is shot and killed by a sharpshooter’s bullet, and the now panicked and disorganized Union forces try to escape the slaughter. As the Union soldiers piled into the three available boats or tried to swim back across the Potomac, the Confederates advanced forward, firing upon them from atop the bluff. The overburdened boats capsized and most of the soldiers who didn’t drown were shot or captured by the Confederates.

While outnumbered 2,000 to 1,600, it was a clear Confederate victory. 921 Union soldiers were killed or drowned. Only 141 were killed on the Confederate side. 553 Union soldiers were captured; the Union took only 2 Confederate prisoners. 150 additional Union soldiers were missing and unaccounted for after the battle.

While the casualty numbers are comparatively low, the political situation was such that yet another Union defeat hit hard.

Out of the disaster of Ball’s Bluff came the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War, a political committee that was to affect every decision by every commander for the remainder of the war. Its chief purpose was to assign blame for military failures.

As the commander in the field was a slain Senator, one of their own, and as McClellan was too far removed from the actual battle, General Stone was chosen to be the scapegoat.